Before we take a deeper dive into the fine points of our statewide Blueprint for North Carolina, it’s worth pausing to define what success would look like. These are the principles that guided us as we designed models for effective and sustainable rural healthcare, as mandated by the General Assembly.

Defining Success

Principles

Effectiveness

Effective healthcare delivery means first and foremost that the supply of healthcare services is sufficient to meet the needs of the local population. If individuals cannot access routine, complex, and emergency healthcare services in a reliable and timely manner, then health outcomes will suffer over time.

The most effective healthcare is local healthcare. When routine services are geographically distant, patients will put off the lower-cost, preventative care that keeps them healthy and out of the hospital. When emergency services are geographically distant, every mile can be a matter of life and death. When complex, specialized services are geographically distant, both length of life and quality of life are negatively affected.

For all of these reasons, the Blueprint establishes accessibility benchmarks for key services. On average, the drive time for rural North Carolinians should be no more than:

- 20 minutes for primary care

- 30 minutes for cancer treatment (preferably tied to a comprehensive cancer program that provides a continuum of care)

- 30 minutes for an Emergency Department

- 60 minutes for maternity care

- 60 minutes for a regional referral center

With resources properly distributed across the continuum, our research shows that these benchmarks are achievable and sustainable for almost all rural residents, with two caveats. First, the American Association of Medical Colleges estimates a current shortfall of 20,000 primary care physicians – and up to 40,000 by 2036. Thus, our targets for primary care are set at 70% of demand – a large improvement over the status quo but still achievable with significant recruitment efforts and public policy support.

Secondly, for a handful of counties in the Outer Banks and far west of the state, drive times may be somewhat longer because a small, scattered population cannot support the needed facilities. Even in these areas, however, residents will enjoy better access under the Blueprint due to optimized distribution in neighboring counties.

Sustainability

Sustainability is not about protecting turf or maintaining the status quo. Indeed, we recognize that the status quo is not an option, and not every rural hospital will still be operational in its present configuration five to ten years from now. The goal of this Sustainability Blueprint is to recognize where change must happen and point the way to an orderly transition. Without that sort of planning, change will still come, but it will be sudden, chaotic, and infinitely more disruptive to rural communities.

Sustainability is about more than mere survival, however. Hospitals and health systems need operating margins that allow for regular investment in providers, equipment, and facilities. Without that investment, care will suffer, patients will look elsewhere, and cutbacks or closure will ensue.

With some planning and foresight, sustainable healthcare providers can evolve their services and right-size their facilities to meet the changing needs of their communities. We call this “stretching the continuum.”

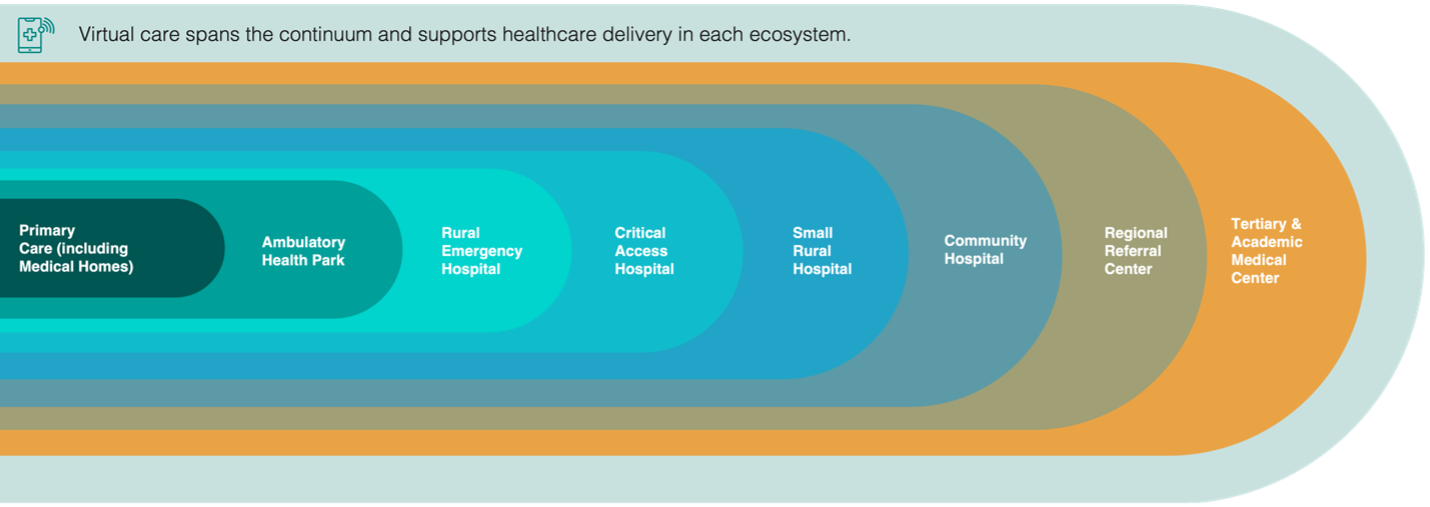

The healthcare continuum starts with services such as primary care that are most used and most general. With each step to the right, patient care becomes slightly more specialized or complex; at the same time, the average patient will use those services less often. So, to take the extremes, many patients will visit their primary care provider twice a year, while two nights in a tertiary hospital might be enough for an entire lifetime.

Much of today’s rural healthcare is delivered in small hospitals that were built decades ago, when communities and consumers were much different. That leaves too many resources focused on low-acuity hospital beds, while important services toward either end of the continuum get squeezed out. In this scenario, none of the competing hospitals can afford to invest in better care. Eventually, one or more of the hospitals will fail with little warning, throwing entire communities into crisis – a crisis that could have been avoided by thoughtfully reimagining delivery systems and making choices based on mission imperatives and the public good.