Rural healthcare delivery in North Carolina presents a complex challenge that defies simple solutions. Our quantitative and qualitative research led to eight findings that challenge common assumptions about rural healthcare and point toward more nuanced, more sustainable approaches for the future.

Findings

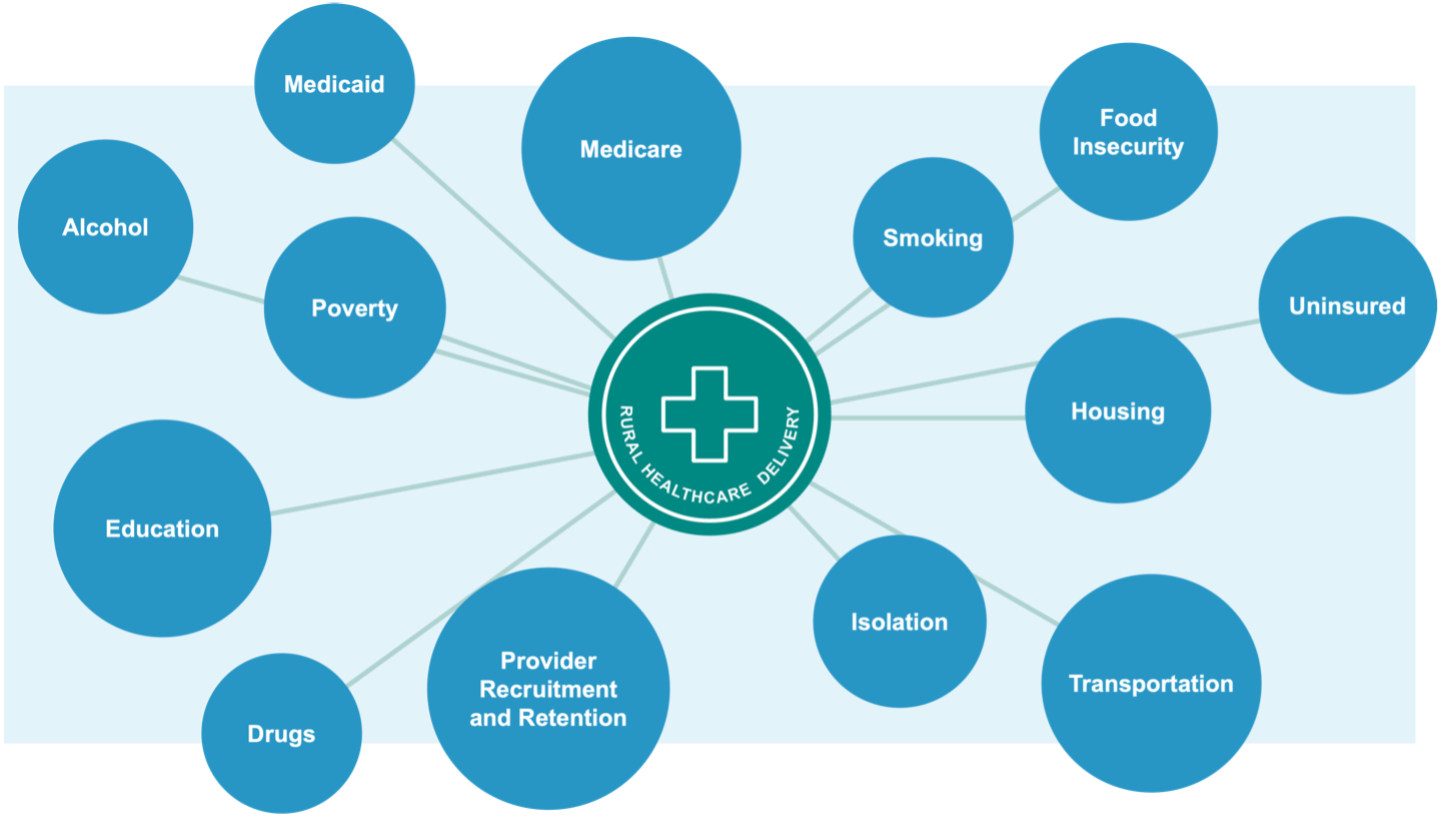

Finding 1: Rural Healthcare Does Not Exist in a Vacuum

In North Carolina, as in every other state across America, rural residents tend to be older, poorer, and less educated than non-rural residents – three factors that are strongly correlated with lower health status.

- Older residents have multiple chronic health conditions that cost more to treat – but retirement often means they no longer have commercial insurance to pay the bills. Aging in a rural community can mean greater issues with transportation, exercise, and social isolation. Older residents may also struggle with virtual care and connected health devices.

- Poorer residents are often uninsured or under-insured, leading them to forego regular checkups and other preventative care. Low-income housing can be unhealthy or dangerous, and diets are heavy on cheap, less nutritious foods.

- Less-educated residentshave lower health literacy, which leads to higher rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, and other risky behaviors that lead to long-term health issues. Lower education is also associated with lower preventative care utilization and lower prescription adherence.

”It is hard to recruit physicians to come to a rural area where there's a perception that there's not as many amenities, not as many resources.

Listening Session Participant, Scotland County

Any one of these factors makes healthcare delivery more complicated, but when communities are older, poorer, and less educated, providers face a tangled web of external variables that cannot be treated with a bandage or a prescription.

Even with a perfect system for healthcare delivery, some health disparities would persist because rural life is simply different than life in other places – and crucially, those differences can make it much harder to attract doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals. Younger, highly educated professionals are often hesitant to move to a community that skews older and less educated; hesitant to leave the amenities of an urban or suburban lifestyle; and hesitant to enroll their children in smaller, under-resourced schools.

This was a theme that came up again and again in every listening session and every conversation that we held across the state: The problems of rural healthcare cannot be solved in isolation. From transportation to housing and education to addiction, so many of the problems facing rural healthcare stem from a persistent lack of economic development. Strong health systems can drive economic development, but the reverse is also true – a weak local economy acts as a drag on the sustainability of rural healthcare.

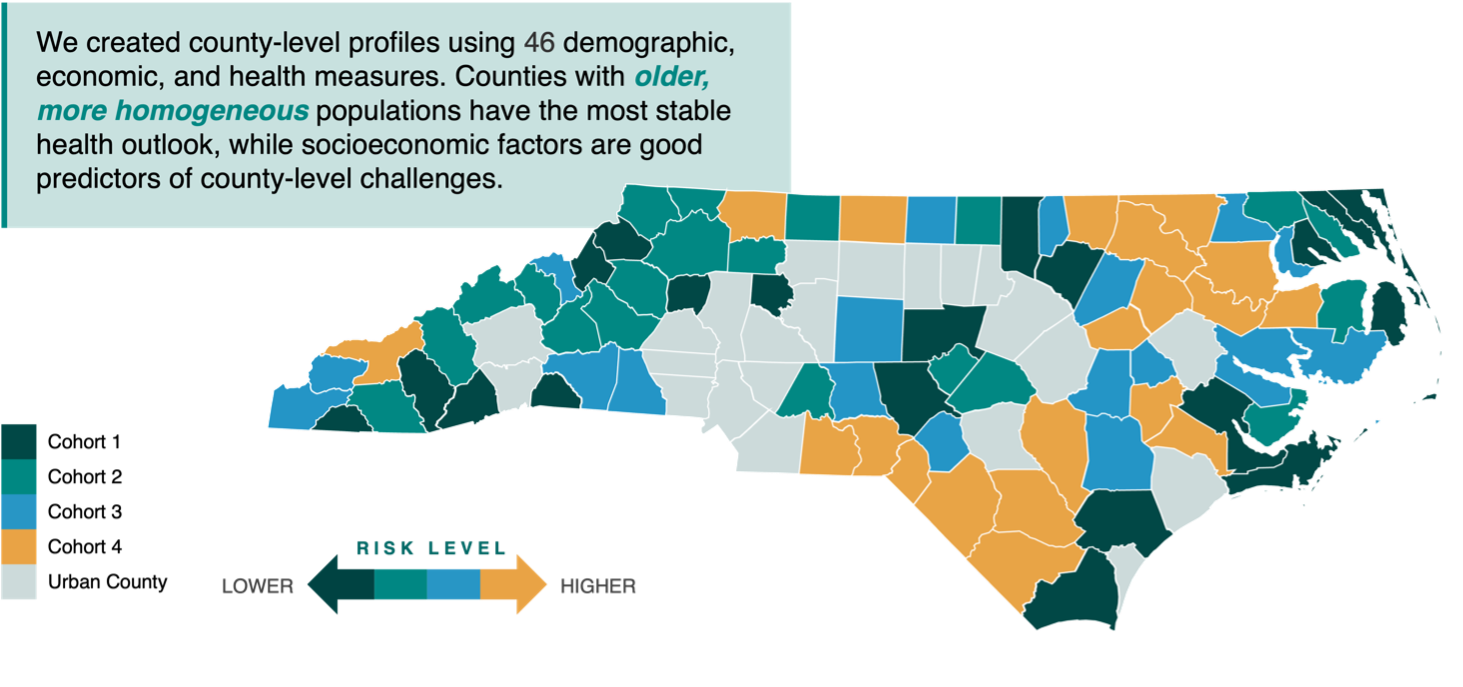

Finding 2: Not All Counties Face the Same Risk

As our research clearly shows, “rural healthcare” cannot be analyzed as a whole. Instead, North Carolina has 78 rural health ecosystems resulting from singular combinations of demographics, economics, education, resources, and opportunities.

Some of the state’s most affluent retirement communities are found in rural counties set along the coast or in the mountains, where more homogeneous populations enjoy robust foundations for health. These residents benefit from key advantages such as English proficiency and health literacy, which facilitate better engagement with the healthcare system. Wealthier retirees also tend to have reliable access to appropriate care when needed.

Just down the road, the picture can look very different for rural counties struggling with multiple interconnected issues. These areas frequently face projected population decline and have higher proportions of non-White residents. Their residents commonly contend with poverty, food insecurity, and transportation disadvantages – all factors that can significantly impact health outcomes before healthcare services even enter the equation.

For healthcare leaders and policymakers, it is crucial to understand which counties are relatively stable and which face the greatest risk. For better data-informed decision making, we created cohort groupings of rural N.C. counties, based on 46 well-established demographic, economic, and health measures gleaned from 15 different data sources.

Cohort 1 counties have the most stable healthcare outlook and are best equipped to deal with sudden changes. Things gradually deteriorate in Cohorts 2, 3, and 4 – a less stable outlook and a greater exposure to systemic shocks.

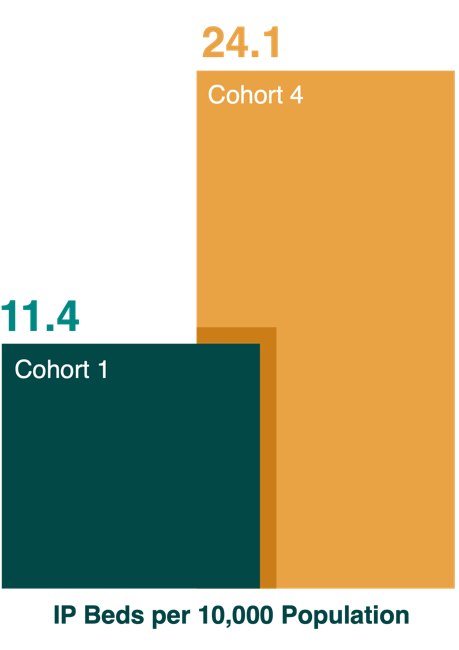

Finding 3: Not All Hospital Beds Are Needed – But Some Are Essential

Many people assume that adding more hospital beds will improve healthcare outcomes in rural areas. However, the data shows quite the opposite: Rural counties with the worst health outcomes actually have the highest rate of acute care and ED beds per capita. They also show the highest rates of preventable hospitalizations. This tells us that bigger hospitals and more beds are not in themselves a guarantee of better health.

Counties where residents face the most severe health challenges already have the most licensed acute care and emergency department beds per capita. They also have the highest rates of preventable hospitalizations.

Financially sustainable rural healthcare requires more of the low-cost, preventative services that people need most often and fewer high-cost, high complexity services such as inpatient care.

Clearly there are hospital beds – and even entire hospitals – that could be downsized with minimal impact on community health. But the opposite is also true. Some hospitals can be characterized as “essential” based on their role in the community. This is not a judgment of the hospital itself, but rather an analysis of overall community need and the larger impact of any closure. By analyzing factors such as geographic isolation, sole provider status, occupancy rates, and community health status, we can create an “essentiality score” that indicates the systemic risk of losing a hospital. To create the Blueprint, we used essentiality scores to double-check the potential impact of any change in service levels.

Generally speaking, hospitals that we characterize as “essential” are found in counties that score lowest on demographic, economic, and health measures – Cohorts 3 and 4, by our definition. Because these counties have a less stable outlook overall, their hospitals tend to play an outsized role. In fact, among the 15 “essential” hospitals statewide, 10 are located in Cohort 4 counties and four are located in Cohort 3 counties.

Ultimately, the decision for configuring healthcare resources should be up to providers of care, local stakeholders, and state policymakers. The Blueprint presents a data-informed picture of healthcare supply and demand in rural North Carolina that is agnostic on details such as ownership or service mix at individual facilities. For these more granular decisions, RHI can offer technical assistance, research support, and strategic expertise to local stakeholders.

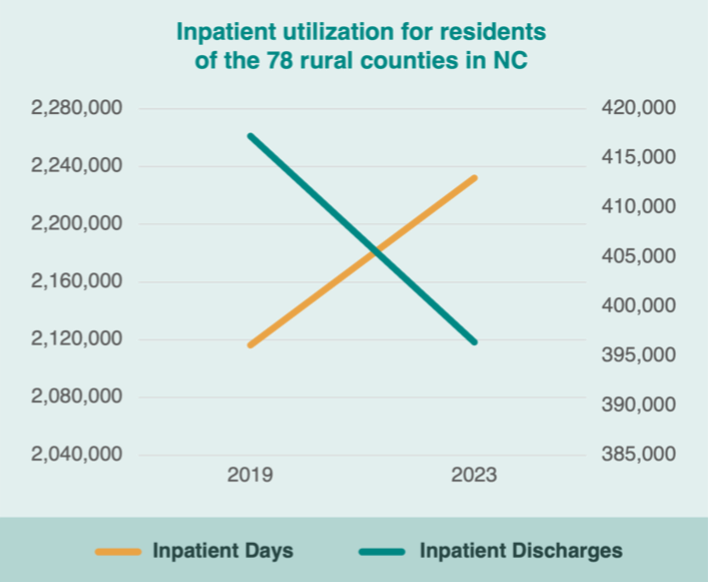

Finding 4: The Nature of Inpatient Care Is Changing

All across the country, “routine hospitalizations” are becoming less routine. From hernias to hip replacements, advances in technology and standards of care have fundamentally altered demand for low-complexity hospital services. Payment pressures are further incentivizing the shift to lower-cost outpatient settings.

This pattern is clearly evident in rural North Carolina, where inpatient discharges have trended downward since 2019 – a trend that puts enormous strain on hospital budgets because of high fixed costs that can only be supported by “heads in beds.” As North Carolinians seek more care outside the hospital setting, rural counties across the state are left with expensive, unused beds that drain scarce resources. Other counties where there is more specialization of services, however, face a deficit of inpatient beds. The Blueprint seeks to address this imbalance.

Beyond the sheer number and distribution of hospital beds, our research also found an important shift in the type of beds that are needed. There is no denying that fewer patients are checking into the hospital, but when they do check in, patients in most cohorts are staying longer – an indication of more severe or more complex medical needs.

With more care shifting to outpatient settings, discharges in NC show a clear downtrend. At the same time, increasing length of stay indicates greater acuity–a warning sign for smaller hospitals treating “routine” cases. These trends suggest hospitals focused on low-acuity inpatient care will be financially unsustainable.

The chart above includes all rural patients, wherever they seek care. Because the local hospital may not offer complex services, many inpatient days (represented by the yellow line) are actually spent in urban or suburban facilities. This has important implications for rural sustainability. With critical access hospitals and small rural hospitals facing declining demand for low-acuity services, the Sustainability Blueprint emphasizes greater access to community hospitals and regional referral centers, where more complex services are the norm.

Finding 5: Sustainability Goes Beyond County Lines

Rural residents don’t live their lives confined within county boundaries, nor do healthcare providers limit their services to a single county. This reality demands a shift from county-based planning to regional planning approaches.

”Folks have to leave the county just to receive basic health care needs much less specialists or anything emergent or more difficult to deal with.

Listening Session Participant, Avery County

If we look purely at the county level, only 47 of 78 counties can financially sustain a hospital. But, when we “zoom out” for a regional view, the outlook changes considerably. There are multiple areas in our state where neighboring individual counties do not have the local demand to sustain a hospital, but if we erase borders to analyze the combined need, a hospital might clearly be called for.

For instance, take Northeast Region B (Gates, Chowan, Perquimans, Pasquotank, Camden, Currituck, Dare). Individually, none of those counties exhibit the kind of demand that would make a hospital financially sustainable, but the region as a whole clearly does have the demand, with a community hospital and two critical access hospitals in operation for a number of years.

The same phenomenon occurs with other services, as well. When we group counties to better reflect real-life travel patterns, the larger population base often is enough to justify adding new services or repurposing existing facilities to better match demand – such as converting a community hospital to a regional referral center. This reality becomes evident again and again in the Blueprint that follows.

Finding 6: For Inpatient Care, Patients Favor Experience and Specialization

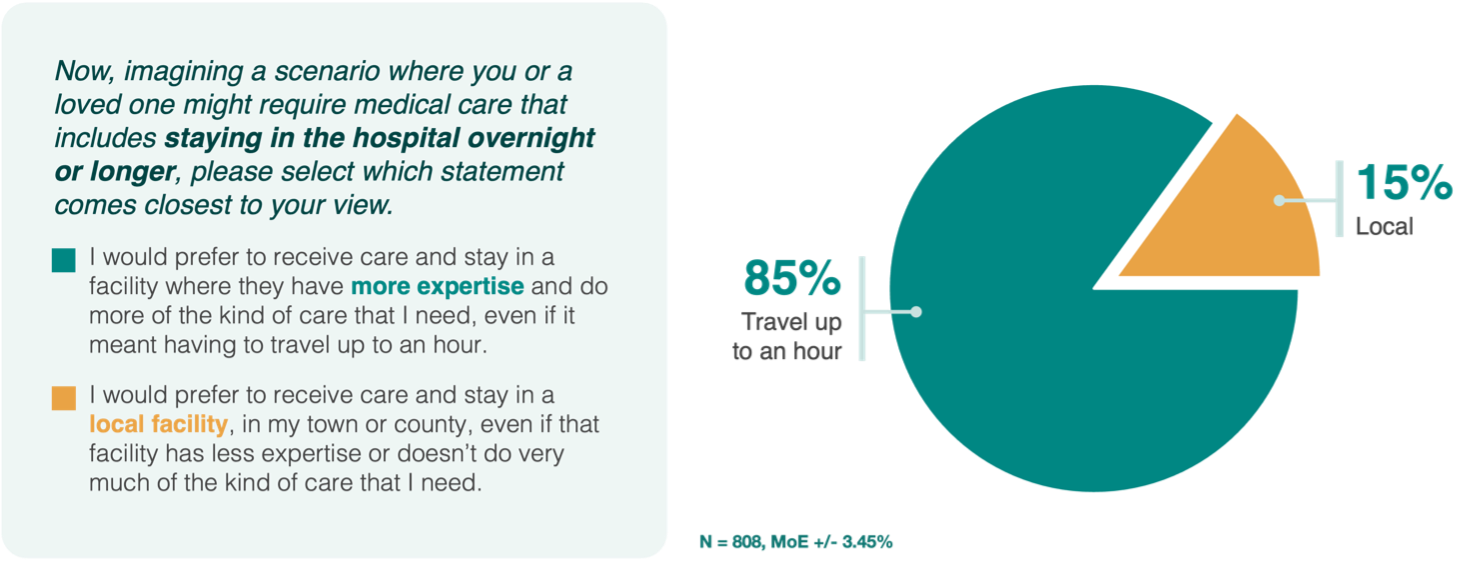

Convenience is not the primary concern for rural residents faced with an overnight hospital stay. In fact, our statewide survey found that respondents are inclined to pass up the closest hospital if they believe that a more distant facility offers more specialized care or more experienced clinicians. This finding supports statewide discharge data showing that 63% of North Carolina residents seek healthcare at a facility outside their home county.

For inpatient care, an overwhelming majority (85%) of survey respondents said they would drive up to an hour for a hospital with greater expertise rather than choosing a local hospital with less expertise. A solid majority (55%) said they have greater trust in clinicians working at a larger facility with more services available, rather than local clinicians working in smaller facilities with fewer services. In other words, rural residents are telling us that they prioritize volume, experience, and specialization when choosing a hospital.

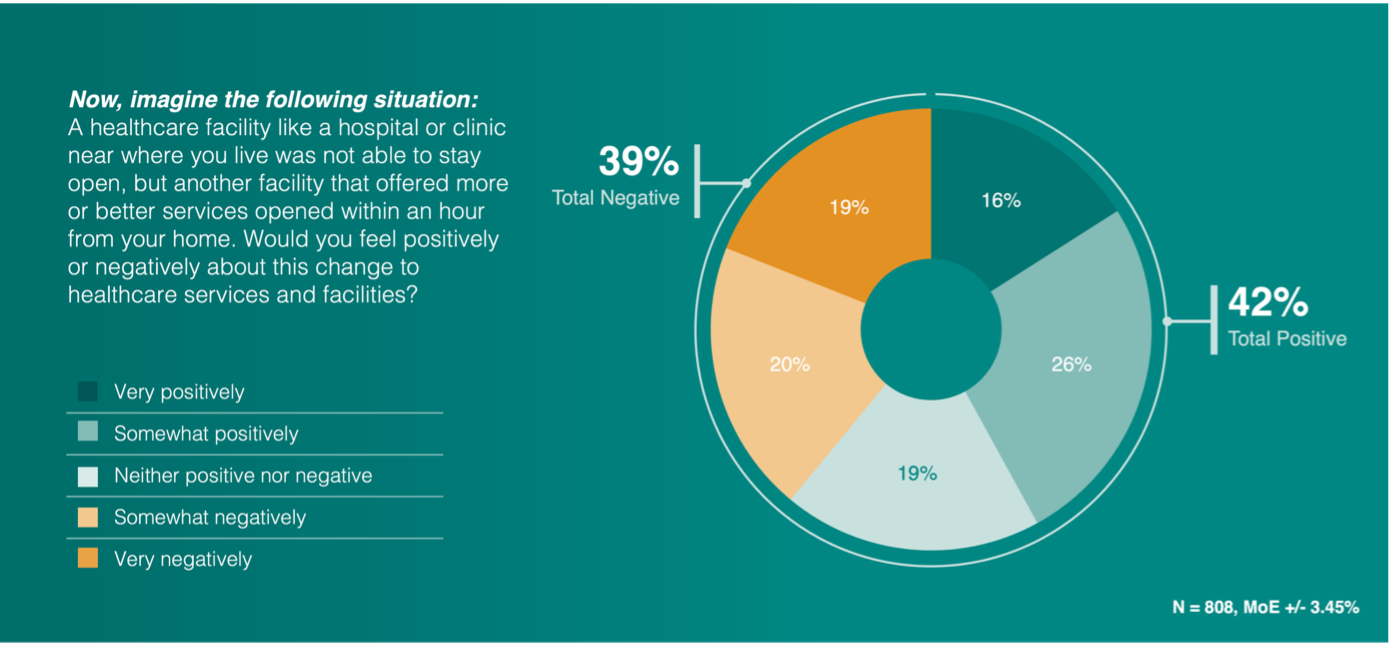

For one final check, we asked the question another way: “Imagine a healthcare facility like a hospital or clinic near where you live was not able to stay open, but another facility that offered more or better services opened within an hour from your home. Would you feel positively or negatively about this change to healthcare services and facilities?”

Only 39% of respondents said they would view it as a negative if their community lost its most convenient hospital but gained more advanced services a bit farther away. Of course, this does not diminish the concerns of those four in 10 rural residents. Local hospitals serve not only as hubs for medical care but also supporters of community activity and major employers. Concerns around closures and service changes reflect this reality and must be addressed.

The bottom line is this: When it comes to choosing a hospital, rural consumers are tipping in favor of specialization, expertise, complexity over convenience or local connection. This strongly suggests that when inpatient care is needed, most rural residents with good transportation options will consider bypassing their nearest hospital if they perceive that “better services” or “more expertise” are available an hour away.

With consumerism on the rise in U.S. healthcare, this will be a growing challenge for smaller, low-acuity hospitals.

Finding 7: For Primary and Emergency Care, Patients Want Proximity and Convenience

”[People] are using 911 as their taxis, and the ER as their PCP.

Listening Session Participant, Pasquotank County

We know from numerous studies that proximity matters in primary care. When people have access to primary care providers within a reasonable distance, mortality rates are lower, chronic conditions are better managed, and there are fewer preventable hospitalizations.

With emergency services, distance can be a matter of life and death. Research indicates a 5-10% increase in mortality for each additional 10 miles of distance to the nearest ED.

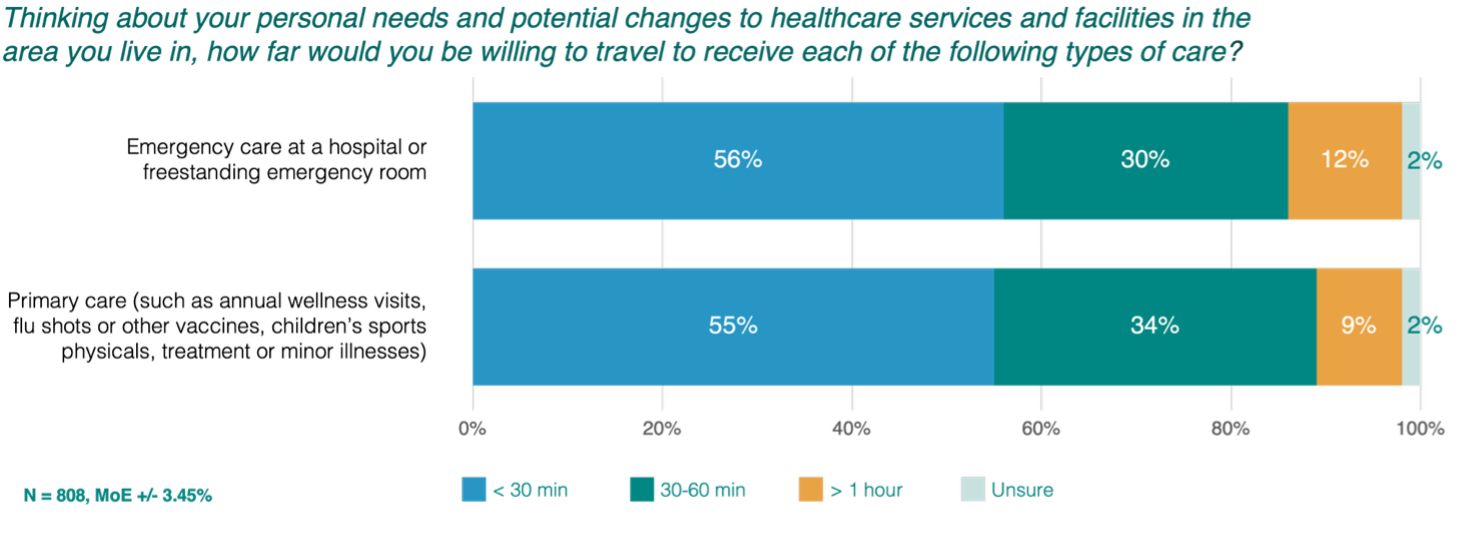

For both primary and emergency care, national studies have found that disparities are especially pronounced in rural communities, so the Blueprint puts particular emphasis on these services, with drive time targets of 20 and 30 minutes, respectively.

Importantly, our survey shows that rural North Carolinians have similar expectations when it comes to accessing primary and emergency care. Clear majorities want to reach their PCP or ED in 30 minutes or less. Achieving those drive times is a major factor in our scoring model for effective, sustainable rural healthcare.

Finding 8: For Key Specialties, Patients See Accessibility as a Problem

”I don't know that there's any specialty that we could really say that we're fully staffed in.

Listening Session Participant, Robeson County

In our survey, 52% of rural residents were satisfied with the quality of care in their community, but only 41% were satisfied with the type of services available. In other words, rural communities lack specialty care, and residents feel the strain.

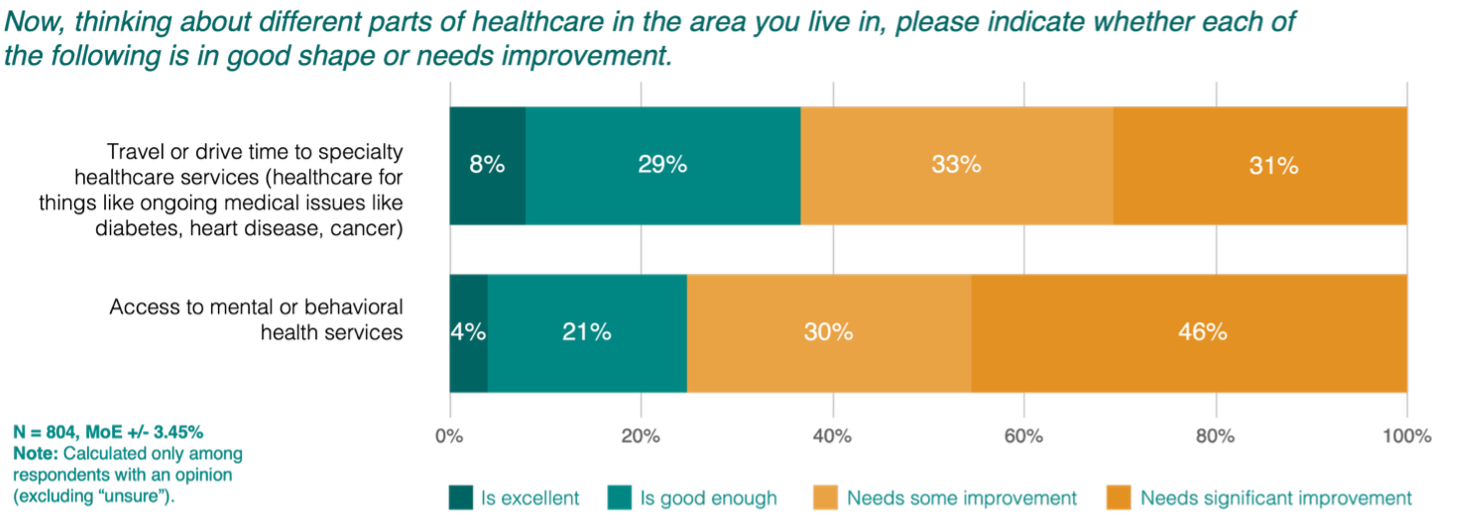

If a quick checkup and an overnight hospital stay represent the two extremes of healthcare delivery, in between those extremes are numerous conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and cancer that require ongoing outpatient visits for specialized care. In our statewide survey, only 37% of respondents who expressed an opinion rated access to specialty services as excellent or even good enough.

We should point out that rural residents understand they will need to travel for specialized services, so low satisfaction is not due to unrealistic expectations. Respondents told us they are willing to drive up to an hour, yet they still are not satisfied with the options in their region.

With mental and behavioral health services, satisfaction levels are extremely low – just 25% of rural residents say their access is excellent or good enough – and quantitative research confirms that perception. Twelve North Carolina regions fall below the state’s rural average for behavioral health access points per capita, even before accounting for the level of service available at each access point. More study is needed to fully understand the access barriers for mental and behavioral care in rural communities and extend the Blueprint to include these core services.

For one last look at specialist provider access in rural North Carolina, we calculated the population need for five additional specialties: general surgery, orthopedics, ophthalmology, cardiology, and gastroenterology. Although these services are generally in high demand among older residents, we did not find one rural region with enough providers to meet the current level of need for all five specialties – even in regions that could otherwise support a regional referral center.

Finally, it is worth noting that these more specialized services often do not need to be provided in the hospital – good news from a cost perspective, since high overhead costs make hospitals a more expensive setting for healthcare delivery. Ambulatory health parks (AHPs) are cheaper to build and cheaper to operate, making them an attractive option for any number of outpatient services. By locating AHPs strategically and distributing services across multiple access points, we can meet both operational needs and community expectations – the very definition of effective and sustainable healthcare.